Cybersecurity is certainly nothing new, but malware has been in the headlines recently. In this opening article on security Holly Williams, a 10-year expert of the infosec wars and a Penetration Test Team Leader, takes a look at the past, present, and future of the dark art.

1971

THE CREEPER: MALWARE’S DAY ZERO

Malware was born in another era, in a server room far away, to a computer you may have never used, running an Operating System you’ve possibly never heard of. In fact, the word “server” wasn’t common currency at the time.

Like so many experiments in technology, CREEPER started benign: a prank by famous coder Bob Thomas, on an early computer (a Digital PDP-10) running software called TENEX that time-shared tasks between cabinet-sized processors. Each had less computing power than a microwave oven today.

All CREEPER did was output a message on-screen – actually, on-teletype – that copied itself to other machines on the simple network. But as a proof of concept, it’s now recognised as the first malware. A piece of code designed for mischief.

More damaging than the simple virus was the idea it gave birth to. As computers shrank in size and gained in power, moving from vast underground bunkers to offices and homes, that idea went forth and multiplied.

1986

BRAIN THINKS ITS WAY INTO OUR DESKTOPS

The next 15 years weren’t devoid of CREEPER’s descendants. But with computers still a rare sight and few connected to each other beyond small LANs, their effects were limited. Until 1986, when Brain started infesting floppy disks on the still-new IBM PC.

Again, Brain wasn’t supposed to be malicious. Written by two brothers in Pakistan, it relabelled and moved a few kilobytes of the floppy’s boot sector – a “header” somewhat akin to a book’s Table of Contents. In doing so it let the brothers control piracy of a commercial software package, and gave phone numbers so legitimate users could disinfect their disks.

But with the ability to make floppy disks unreadable, Brain went beyond CREEPER, since it wasn’t just sending a piece of text whizzing around – Brain executed code. It was actual malware, the first true virus. Brain’s legacy lives on in every illicit virus circulating today.

And what happened to those early malware pioneers? They’re still in business today, running an Internet Service Provider in Pakistan. Apparently they still get calls from time to time.

1989

THE AIDS EPIDEMIC

Up to this point something was missing from the history of malware: actual malice. That all changed in 1989, when Joseph Popp created the first true ransomware.

Its creator, strangely, was a health worker with a Harvard PhD. Masquerading as a free application to check a person’s susceptibility to HIV, sent out for free on 5.25” floppies to 20,000 addresses, the virus was – with extreme political incorrectness – called the AIDS Trojan. Once aboard a disk, it scrambled data into an encrypted volume and only a payment would decrypt it. The price was $189, payable to a Panama PO Box.

Luckily, few users suffered, although one Italian research facility reportedly lost a decade of data because their code was badly designed and allowed decryption without payment. But as the first ransomware, it left thousands of researchers frustrated, confused, and angry.

What of Popp? Few clues exist as to why he unleashed ransomware on the world, but perhaps it had something to do with being rejected for a job in AIDS research at the World Health Organisation. While he never paid for his crimes, he may still have suffered for them: he was found mentally unfit for trial in 1991, in part due to his habit of wearing cardboard boxes on his head.

1989-PRESENT

RED IN TOOTH AND CLAW

In the 1990s, ransomware gained an evolutionary advantage. Public-key cryptography meant a single “key” retained by the ransomware creators could unlock millions of scrambled disks, but only in conjunction with a second “key” purchased by the victim. In other words, your ransom payment would unlock just one computer: yours.

At this point, cybercrime became scalable. Then, in 1995, the ecological niche exploded as millions of computers – no longer the preserve of academia – starting connecting to a splashy new bulletin-board-on-steroids called the World Wide Web.

Today, ransomware is perhaps the most insidious threat to a connected individual’s work. It seals their data – and often their livelihood – inside an encrypted vault, while payment is only accepted in BitCoin or other virtual currencies, leaving no trail in the formal banking system.

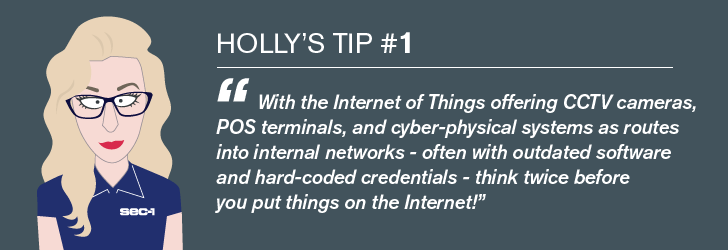

And there’s a plethora of routes into your data when everything is connected to everything else. A breach may come via the Internet of Things. Bring Your Own Device. Cloud services. Point-of-Sale terminals. CCTV cameras. Industrial control systems. (Home Depot was breached from a single compromised POS terminal.) Any device can be a door into corporate data, and some can’t even be locked.

So the next five years signal another shift: towards machine learning, or AI. Soon, attack software will learn. Not just sniff around, or mindlessly flood your server, or brute-force your passwords, but adapt itself to attack where you’re most vulnerable.

THE FUTURE

HOPE SPRINGS ETERNAL

Fortunately, there is something about evolution. As the attacks have become more powerful, so have the defences. The majority of work computers have virus software installed; most users know to keep patches and updates current; people are willing to learn, if you just explain why.

In addition, the same technologies that enable malware – public-key cryptography, IP tunnelling, cross-site scripting – can also be used to fight it. Millions of professionals store their own data on encrypted volumes that can’t be maliciously tampered with; around a fifth of desktops have full hard disk encryption; antivirus software vendors cover hundreds of millions of machines, learning from every hack attack and offering updates every day against the latest threats.

So ransomware, while always a risk to today’s business, can be defanged – with sensible security policies and active monitoring of your network configuration, even in a world of BYOD and Shadow IT. So if you’re ever depressed by the thought of malware, remember that fightback is possible.

Alternatively, you could put a cardboard box over your head, just like Joseph Popp.

Want to know more? Take a look at Cyberphobia by Edward Lucas.